茲卡病毒感染可能導致新生兒頭部異常地小。目前為止,還沒有疫苗或藥物可治療茲卡病毒。不過美國聖路易華盛頓大學醫學院科學家上月底發表研究結果指出,登革熱病毒的大Y型蛋白質抗體在小鼠身上能有效防堵茲卡病毒。

病媒蚊相同 科學家從登革熱找茲卡病毒抗體

巴西等茲卡病毒嚴重肆虐的地區,同時也是登革熱疫區,而且兩種病毒的病媒蚊相同。

茲卡和登革熱透過埃及斑蚊(Aedes aegypti)和白線斑蚊(Aedes albopictus)叮咬傳播。這兩種蚊子在白天和黑夜都會叮咬人。根據美國疾病控制和預防中心的資料,茲卡也會透過性行為傳播,並從懷孕婦女轉移到胎兒。

現在研究人員希望從這種抗體發展出能保護胎兒免受茲卡病毒感染的藥物。

研發抗體藥物 女性可在懷孕期間保護胎兒

抗體藥物的使用已經有數十年的歷史,能夠暫時抵抗狂犬病等傳染病,也是沒有疫苗可用時的解決方案,如茲卡病毒這類傳染病。以抗體作為茲卡預防藥物的關鍵在於,可使女性血液中持續含有足量的抗體,以在懷孕期間保護胎兒。

研究人員表示,抗體能在血液中留存數週,因此在婦女孕期中給予一或多劑抗體藥物,可以保護她的胎兒免受茲卡傷害,另外也能保護懷孕婦女免於茲卡和登革熱。

研究作者之一戴門(Michael Diamond)博士說:「我們發現這種抗體不僅能降低登革熱病毒的傷害,在小鼠身上也可以保護胎兒免受茲卡傷害。」

該研究於9月25日發表於《自然免疫學》期刊。

小鼠實驗 登革熱抗體可能對茲卡病毒有用

由於登革熱和茲卡間有所關聯,華盛頓大學研究人員推測,登革熱抗體可能對茲卡也有用。

戴門和研究生費南德茲(Estefania Fernandez)與倫敦帝國理工學院醫學博士史奎頓(Gavin Screaton)合作,成功在數年前開發出一組人類登革熱抗體。

科學家用茲卡病毒感染非妊娠成年小鼠,在感染後一、三或五天內給予登革熱抗體;同樣感染茲卡病毒的控制組小鼠則給予安慰劑。在感染三週內,超過80%未經治療的小鼠死亡,而在感染後三天內接受登革熱抗體的所有小鼠仍然存活。感染後五天接受抗體的小鼠中有40%存活。

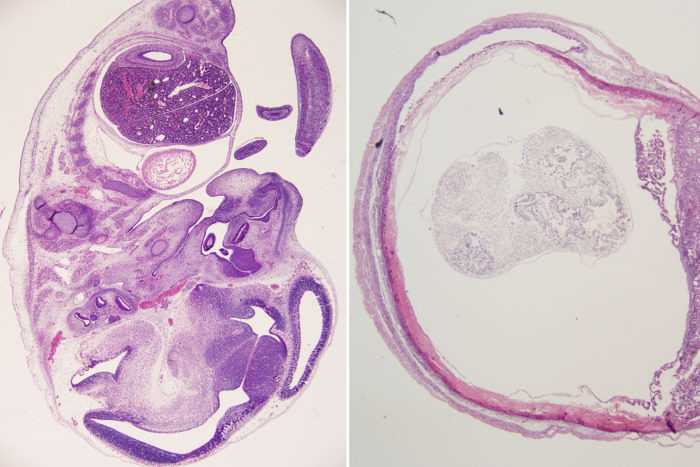

為了確定抗體是否能夠保護胎兒免受感染,研究人員以茲卡病毒感染妊娠第六天的母小鼠,在感染一或三日後給予同樣劑量的抗體或安慰劑。

在妊娠第13天,感染隔天就接受抗體的小鼠,胎盤內茲卡遺傳物質數量是控制組的1/60萬,胎兒頭部的茲卡遺傳物質數量是1/4900。然而,感染後三天給予抗體的效果較差,胎兒頭部的病毒遺傳物質量是控制組的1/19,胎盤中是1/23。

結果顯示,為了有效保護胎兒免受茲卡病毒影響,必須在感染後儘快治療。這在臨床上可能難以實現,因為婦女很少知道什麼時候被感染。但是一旦知道懷孕就給予抗體,就可以提供立即的防禦措施。

突變改良後 一種抗體對抗兩種病毒

戴門和團隊正在努力確定孕婦需要多少抗體來確保她的胎兒受到保護。同時,科學家們也正在研究如何擴大血液中抗體的半衰期,減少需要給予的次數。

儘管如此,在血液中循環數月的登革熱抗體仍存在風險,因為如果此時被另一種登革熱菌株感染,那麼防止一種登革熱病毒的抗體有時會惡化症狀。

登革熱導致兒童和成人發燒、嚴重頭痛、關節和肌肉疼痛,但不會直接危害胎兒。

為了避免意外加重病情,研究人員在四個位點突變抗體,使得抗體無法加劇登革熱病情。「所以現在我們有一種抗體可以對抗兩種病毒,並且可以安全用於登革熱流行地區,因為它不會使登革熱病情惡化。」戴門說。

An antibody that protects against the dengue virus has also proved to be effective against the Zika virus in mice, scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis announced Wednesday.

Antibodies are large Y-shaped proteins. They are recruited by the immune system to identify and neutralize foreign objects such as viruses.

Brazil and other areas hardest hit by the Zika virus, which can cause babies to be born with abnormally small heads, also host the dengue virus, which is spread by the same species of mosquito.

Zika and dengue are spread by the bite of an infected Aedes species mosquito (Ae. aegypti and Ae. albopictus). These mosquitoes bite during both the day and the night. Zika can be transmitted during sex and passed from a pregnant woman to her fetus, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Until now there has been no vaccine or medicine to treat the Zika virus. But now researchers are hopeful that the discovery of this antibody could lead to a drug that could protect a fetus from Zika infection.

Antibody-based drugs have been used for decades to provide temporary protection against infectious diseases such as rabies when there is no time to vaccinate or, as in the case of Zika, when there is no vaccine available.

The key to using this antibody as a preventive drug would be to make sure that antibody levels in a woman’s bloodstream stay high enough to protect her fetus for the duration of her pregnancy.

Antibodies remain in the bloodstream for weeks, so one or a few doses of an antibody-based drug given over the course of a woman’s pregnancy could protect her fetus from Zika, with the added benefit of protecting her from both Zika and dengue disease, the researchers said.

“We found that this antibody not only neutralizes the dengue virus but, in mice, protects both adults and fetuses from Zika disease,” said Professor of Medicine Michael Diamond, MD, PhD, the study’s senior author.

The study is published September 25 in the journal “Nature Immunology.”

Since dengue and Zika are related viruses, the Washington University researchers reasoned that an antibody that prevents dengue disease may do the same for Zika.

Diamond and graduate student Estefania Fernandez collaborated with Gavin Screaton, MD, DPhil, of Imperial College London, who had generated a panel of human anti-dengue antibodies years before.

The scientists infected nonpregnant adult mice with Zika virus and then administered one of the anti-dengue antibodies one, three or five days after infection.

For comparison, another group of mice was infected with Zika virus and then given a placebo.

Within three weeks of infection, more than 80 percent of the untreated mice had died, whereas all of the mice that received the anti-dengue antibody within three days of infection were still alive. Forty percent of those that received the antibody five days after infection survived.

To find out whether the antibody also could protect fetuses from infection, the researchers infected female mice on the sixth day of their pregnancies with Zika virus and then administered a dose of antibody or a placebo one or three days later.

On the 13th day of gestation, the amount of Zika’s genetic material was 600,000 times lower in the placentas and 4,900 times lower in the fetal heads from the pregnant mice that were treated one day after infection, compared with mice that received the placebo.

However, administering the antibody three days after infection was less effective: It reduced the amount of viral genetic material in the fetal heads 19-fold and in the placentas 23-fold.

These findings suggest that for the antibody to effectively protect fetuses from Zika infection, it must be administered soon after infection. Such a goal may be unrealistic clinically because women rarely know when they get infected.

But giving women the antibody as soon as they know they are pregnant could provide them with a ready-made defense against the virus should they encounter it.

Diamond and colleagues are working on identifying how much antibody a pregnant woman would need to ensure that her fetus is protected from Zika.

The scientists also are exploring ways to extend the antibody’s half-life in the blood, to reduce the number of times it would need to be administered.

Having anti-dengue antibodies circulating in the bloodstream for months on end poses a risk, though, because antibodies that protect against one strain of dengue virus sometimes worsen symptoms if a person is infected by another dengue strain.

Dengue causes high fever, severe headaches, and joint and muscle pain in children and adults but does not directly harm fetuses.

To avoid the possibility of accidentally aggravating an already very painful disease, the researchers mutated the antibody in four spots, making it impossible for the antibody to exacerbate dengue disease.

“So now,” he said, “we have a version of the antibody that would be therapeutic against both viruses and safe for use in a dengue-endemic area, because it is unable to worsen disease.”

※ 全文及圖片詳見:ENS