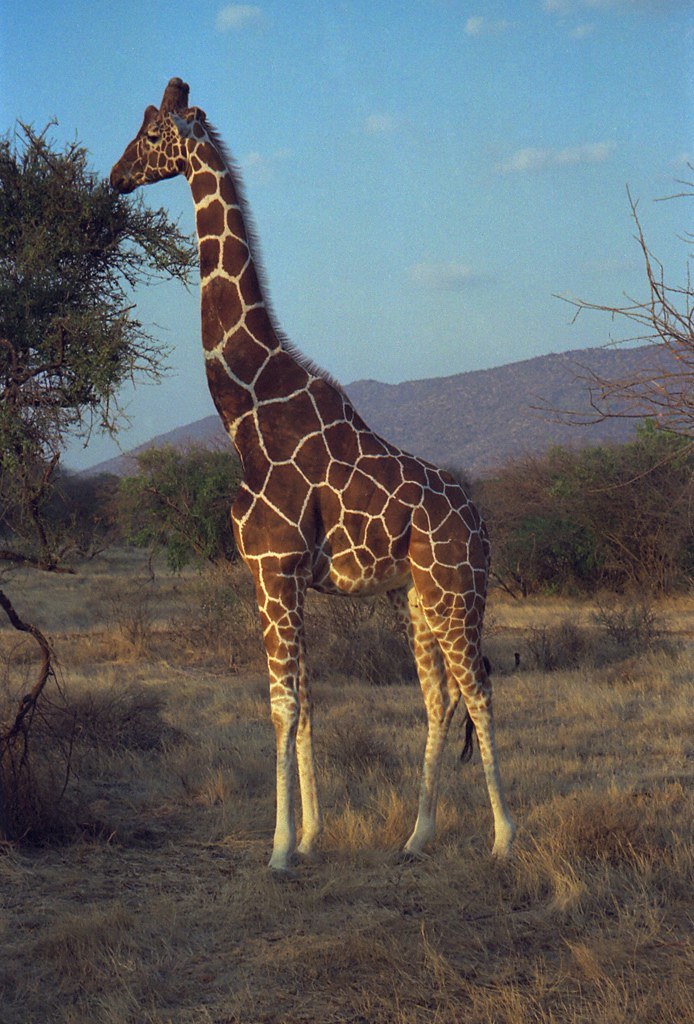

The Giraffe

Classification:

Order: Artiodactyla

Family: Giraffidae

Genus: Giraffa

Species: Giraffa camelopardalis

Subspecies:

G. c. antiquorum (Kordofan Giraffe),

G. c. angolensis (Namibian Giraffe),

G. c. camelopardalis (Nubian Giraffe),

G. c. giraffa (South African Giraffe),

G. c. peralta (West African Giraffe),

G. c. reticulata (Reticulated Giraffe),

G. c. rothschildi (Rothschild's Giraffe),

G. c. thornicrofti (Thornicroft's Giraffe),

G. c. tippelskirchi (Masai Giraffe)

Characteristics: The tallest mammal with an uncertain future

Population Trend: Decreasing

The global giraffe population is estimated to have decreased from around 150,000 in 1985 to fewer than 100,000 in 2015. It represents a slip of more than 30% in three decades[1].

This global figure needs to be looked at more carefully. Among the nine subspecies, four have seen their populations decreasing, four increasing while one has remained stable.

The most significant reduction in population has occurred among subspecies present in Eastern Africa, while Southern African subspecies have seen their populations expanding.

Main Threats:

- Habitat loss due to demographic pressure and land use for farming

- Habitat loss due to human activities such as mining

- Disturbance caused by civil unrest and guerillas

- Traditional hunting for pelts and tails used as ornaments[3]

- Hunting for bush meat

- Climate change inducing modification of giraffes biotopes

A mythical animal with ancestral roots in Eurasia

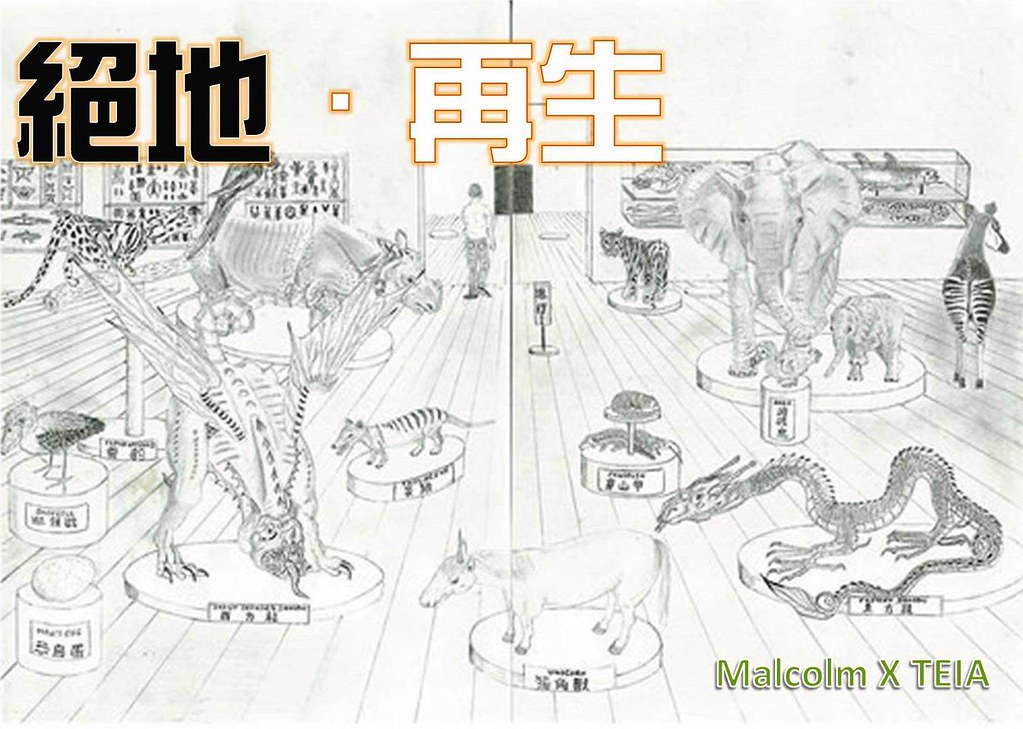

Giraffes and okapis are the only contemporary members of the Giraffidae family.

The first Giraffidae appeared around 25 millions years ago during Miocene. Although there are no members of the Giraffidae outside Africa today, these early ancestors initially thrived in Eurasia.

While giraffes live in savanna biotopes in both northern and southern hemispheres, the elusive okapi is endemic to the tropical rainforests of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Giraffes were already known to ancient Greeks through their relations with Egypt as Egypt constituted a communication bridge between the Mediterranean basin and Subsaharan Africa.

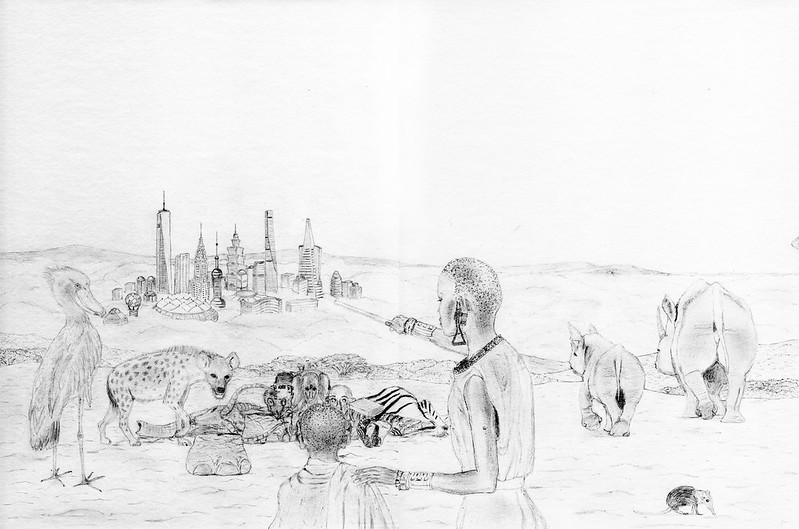

Admiral Zheng He(鄭和) is said to have brought a living giraffe to China in 1414 from his expeditions along the coasts of East Africa. The first descriptions of giraffes associated them with the mythical Qilin(麒麟), a chimera part of Chinese and East Asian cultures.

During the 19th century, their distinctive long neck became a recurring subject of debates among naturalists. Several theories were put forward to explain the mammal's unusual morphology, including those of Charles Darwin and French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck.

Nowadays, giraffes still get the attention of scientists. In particular, their cardiovascular system is powerful enough to pump blood up to a height of two meters[4] , a unique case in the world of mammals. Thanks to Genomics, scientists are getting a better understanding of the evolution processes that have allowed this outstanding machinery to work as it does[5].

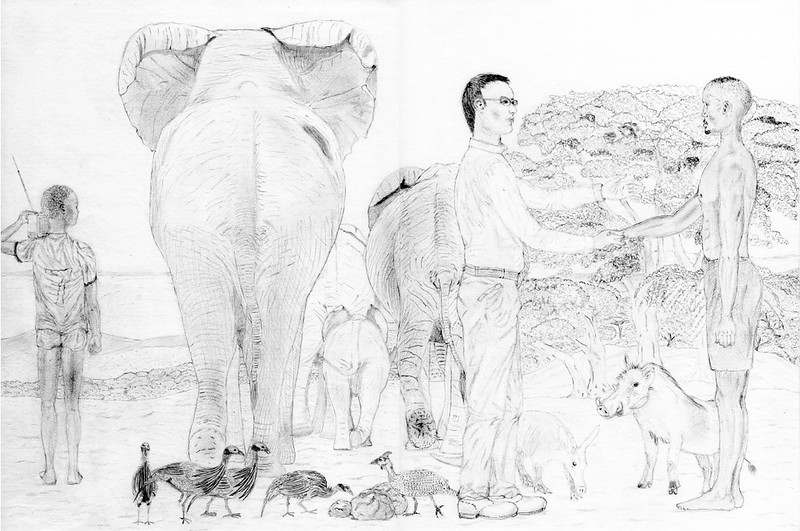

Encounter with giraffes, a personal experience

On December 2016, the classification of giraffes as a vulnerable species by the IUCN was reported in the media.

On a late afternoon of September 1999, somewhere on the long straight road from Chobe River National Park, Botswana, I was seating in a van on my way back to Victoria Falls, Zambia.

I had spent two short days discovering the beauties of Chobe River National Park. Resting in the van, I would not have been able to remember the exact number of elephants, adult and young I had seen foraging for food in the dusty landscape of north-western Botswana or bathing in Chobe River at sunset.

I had been amazed at the rich biodiversity of this dry sandy savanna around the river shores and had not expected the biting cold temperatures at night. The wildlife seemed to be thriving in a rough yet pristine environment.

Exhausted by the night safaris and the lack of sleep during the last days, I was gently discussing with my fellow traveller. She was an American citizen of Seattle, who had travelled all the way to Zambia to take part to an international AIDS conference.

Once you have spent a few days trying to spot wild animals, your eye gets an unconscious ability to detect all shapes that could be hidden animals. My eye had become a bit too imaginative as I remember being distracted several times at the sight of possible warthogs and antelopes on the road sides. They just happened to be plain rocks or logs emerging from the vegetation...

For this reason, I did not mention my fellow passenger nor the local driver about the giraffe shaped-like branch emerging from the bushes. I was lost in my thoughts when the branch quivered and moved forward. In a few seconds, the unexpected happened: a young giraffe had left the vegetation cover and had dared cross the dusty road.

With a feeling of helplessness, I could only wish the driver would be able to avoid a collision.

That was not enough, despite the strong braking, the windshield turned opaque white while we felt the shock. We, passengers, looked through the side-window and could see the gracile young giraffe trying to conceal in the bushes on the other side of the road. She was wounded, one of her leg completely broken and jittering in pain. Mother giraffe had prudently stayed on the safe side and her eyes were following the agony of her calf.

As we went to a complete stop, she gracefully crossed the road to look after her young one.

We, tourists, were focused on the poor animal and soon felt how our concerns were far from the driver's. He was holding his head with both hands, lamenting on the damages made on his van. He would have a hard time announcing the news to his boss.

As for us, useless as we were, we were trying to locate the young giraffe. My fellow traveller even wanted the driver to call a vet... in the middle of the savanna...

I was struck by a sense of fatality intensified by the surrounding rough beauty...Everything had turned silent, the air had cooled down, it was just warm then while the golden streaks in the sky were already announcing the end of the day... In an hour or so, it would be total darkness, the air would be biting cold again, and I felt that the harsh rules of life would lead our young giraffe to her tragic end.

I had experienced one of the threats that giraffes are now more and more facing: encroachement with humans.

Giraffe subspecies: different places, different fates

In the light of DNA analysis, the classification of giraffes is still being debated. The IUCN considers that all giraffes belong to a single species Giraffa camelopardalis. Up to nine subspecies of G. camelopardalis have been identified. They can be distinguished by morphological features as well as differences in fur colour, spotting patterns etc. Hybrids between subspecies are not uncommon, especially in captivity.

Subspecies G. c. tippelskirchi, commonly referred as the Masai giraffe is the tallest and the most numerous one (around 35,000 individuals in 2016) although its population was halved compared to historical estimations[1].

The situation is even worst for Eastern Africa subspecies G. c. camelopardis with a remaining population of just 650 individuals in 2016, down from a population slightly over 20,000 in 1979/1981 [1].

The giraffes I had seen (Botwana and Zambia) belonged to subspecies G. c. angolensis and G. c. giraffa. They are less threatened that the ones in Eastern and Central Africa. Their global conservation is satisfactory as both subspecies have experienced a growth of around 160% from 1985 to 2015 [1].

As of August 2017, the Democratic Republic of Congo (Central Africa) had a single remaining population of giraffes (subspecies G. c. antiquorium or Kordofan Giraffe). The ongoing armed conflicts in the region make this remnant population particularly vulnerable, impairing any conservation measures. This subspecies also subsists in Central Africa, though its global population is on a decreasing trend.

Success in giraffes protection exists outside southern Africa though. Under the auspices of a national conservation strategy, Niger has so far managed to protect the last remaining West African giraffe population (G. c. peralta), increasing it from a mere 50 individuals in the 1990's to around 400 in 2017. This achievement is especially remarkable as Niger belongs to one of the poorest countries in the world.

Thanks to a strong involvement of local communities, giraffes have been given a chance to thrive again. At the same time, ecotourism has been boosted by the presence of the rare mammals, therefore benefiting these communities.

|

Subspecies |

Range |

Population trend |

Striking facts |

|

G. c. angolensis Namibian Giraffe |

present in the area where borders of Namibia, Botswana, Zambia and Zimbabwe meet |

increasing |

Population has more than doubled between 1985 and 2015 |

|

G. c. antiquorum Kordofan Giraffe |

northern Cameroon, southern Chad, Central African Republic and a small remnant population in the Democratic Republic of Congo |

decreasing |

Particularly affected by civil unrest and armed conflicts, its population was estimated at around 2000 individuals in 2016 |

|

G. c. camelopardalis Nubian Giraffe |

South Sudan, south-western Ethiopia |

decreasing |

Once the second most numerous subspecies, it has experienced a drastic fall of 97% between 1980 and 2016, now numbering around 600 individuals[1] |

|

G. c. giraffa South African Giraffe |

northern South Africa, southern Botswana, Zimbabwe, south-western Mozambique |

increasing |

Population has more than doubled between 1985 and 2015 |

|

G. c. reticulata Reticulated Giraffe |

northern Kenya, southern Ethiopia and Somalia |

decreasing |

Considered by some as the most beautiful giraffe due to its distinctive spotting pattern Once estimated around 40,000 individuals, numbering just 8,500 in 2016[1] |

|

G. c. rothschildi Rothschild's Giraffe |

Kenya, Uganda |

slowly increasing |

Protected in Kenya and Uganda, numbering around 1,600 in 2016[1] |

|

G. c. peralta West African Giraffe |

Southwestern Niger |

increasing |

Used to be widespread throughout the Sahel before World War I, now reduced to a single population in Niger[3] |

|

G. c. thornicrofti Thornicroft's Giraffe |

Luangwa Valley (Zambia) |

stable |

One of the rarest giraffes with G. c. peralta, restricted to a single population |

|

G. c. tippelskirchi Masai Giraffe |

Kenya, Tanzania |

decreasing |

The tallest giraffe subspecies and therefore the tallest animal on Earth Still the most common subspecies despite a worrying slip of about 50% in the last fifty years |

Still, challenges remain for this rare Giraffe subspecies.

The long term survival of such a small population is not secured, as it is less resistant to potential epidemics and more prone to defects due to its smaller gene pool.

Climate change and human pressure are also limiting the extension of suitable biotope in this area of Niger.

An increasing awareness of African countries for giraffes conservation

As of August 2017, Niger was still the only African country to have put in place a national conservation strategy for the giraffe. Involving local communities in the conservation programms, it has proved successful, allowing the small population to be multiplied about 8 times in less than 3 decades.

Kenya, home to three giraffe subspecies, is finalising its own national giraffe conservation strategy[1][6].

Rothschild's giraffes are currently protected in Kenya and Uganda.

So far, Southern African countries have been successful in protecting their giraffes population without putting in place any governmental conservation strategy. Giraffes are often translocated and sold between owners of privately owned parks[1].

It is to hope that Niger's success will set an example in the conservation of giraffes and that more countries will be sensitive to their fate. Challenges remain plentiful, including political unstability, demographic pressure and loss of biotopes.

What can I do as a simple citizen?

As one of the last remaining representative of the Earth megafauna, giraffes are a unique living heritage that shall be passed to the future generations.

To give giraffes a chance, here are a few thoughts and recommandations :

- Never buy any product made of giraffe body parts or organs, whether it be a decorative item, a ritual item or a medicine.

- If you can afford it, support ecotourism and give your children the chance to see those wonderful animals in the wild. This includes ecotourism in countries such as Niger, Ethiopia, Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Namibia and South Africa to spot the different subspecies of giraffes.

- If you feel particularly concerned by the fate of giraffes, you can donate to foundations involved in their protection, speak out about the threats they are facing to your friends.

Reference

- IUCN紅皮書:長頸鹿

- African Wildlife Foundation: Giraffe

- African Wildlife Foundation: West African Giraffe

- BBC News: 'Supercharged' heart pumps blood up a giraffe's neck

- PennState Eberly College of Science: How did the giraffe get its long neck? Clues now revealed by new genome sequencing

- Giraffe Conservation Foundation: East Africa Programme Quarterly Report (Jan – Apr 2017)