有研究透過衛星資料發現,2016年非洲的熱帶土地共釋放了近60億噸二氧化碳。這表示,如果熱帶非洲是一個國家,將是全世界第二大二氧化碳排放國 ,比超過美國每年排放53億噸二氧化碳還高。

一篇發表在《自然通訊》(Nature Communications)期刊的報告指出,該地區2016年的排放量「出乎意料地大」,因為熱帶非洲陸地表面多是熱帶森林和泥炭地覆蓋,通常能從大氣中吸收大量的二氧化碳。

科學家表示,這可能與強大的聖嬰現象有關。聖嬰現象是一種自然現象,時不時影響世界各地天氣。在非洲熱帶地區,它可能導致異常高溫和乾旱。

該研究稱,高碳排的其他原因可能包括「大規模土地利用變化」,像是森林砍伐和與農業有關的火災。

熱帶風暴

非洲坐擁全世界三分之一的熱帶雨林。熱帶森林能夠儲存大量的二氧化碳,因為樹木在光合作用過程中從大氣中吸收碳,用以生出新的葉子、枝條和根。

非洲大陸還有全世界約3%的泥炭地,包括全世界最大的熱帶泥炭地。泥炭地是潮濕滯水的環境,可以容納大量土壤中的碳。

雖然非洲熱帶地區是全球重要的碳儲存庫之一,但很少有研究調查該地區土地的年度二氧化碳排放量。

這項新研究分析了兩顆衛星在2014~2017年間記錄下的非洲熱帶陸地碳排放,分別是日本的溫室氣體觀測衛星(GOSAT)和美國太空總署的軌道碳觀測站(OCO-2)。

研究的主要作者、愛丁堡大學地球科學研究員帕瑪(Paul Palmer)教授表示,從這兩顆衛星的資料顯示,非洲熱帶地區的某些部分現在排碳大於吸碳:

「這是一個新視角。其他衛星資料顯示該地區土地大量劣化,但我們的研究首次將地表的過程與二氧化碳變化連結起來。資料顯示,熱帶非洲的某些地區不但正在劣化,還開始釋出碳。」

森林通量

結果顯示,2015年和2016年,非洲熱帶土地的二氧化碳淨排放量分別為54億噸和60億噸(這個數字已納入土地吸收和排放的二氧化碳量的差異。)

整個熱帶地區,2015年和2016年的二氧化碳淨排放量分別是38億噸和59億噸。

這是因為熱帶非洲的碳排放被其他熱帶地區抵消了,像南美洲部分地區在2015年至2016年期間是二氧化碳淨吸收者(即「碳匯」)。

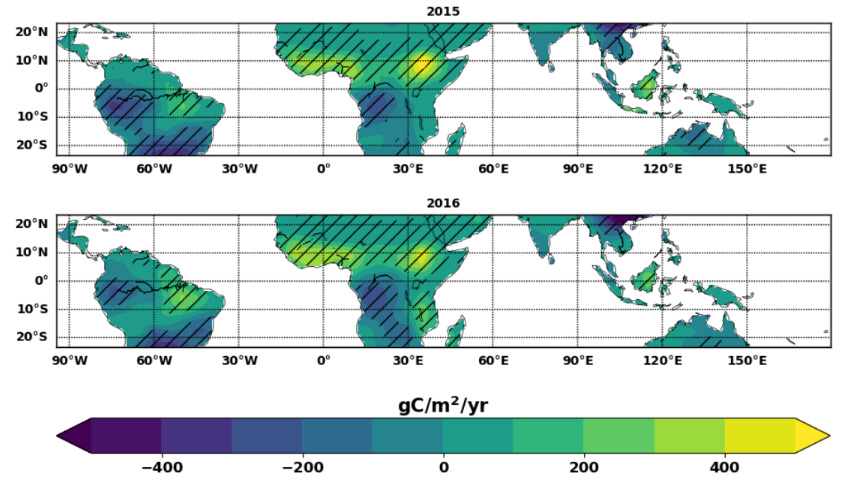

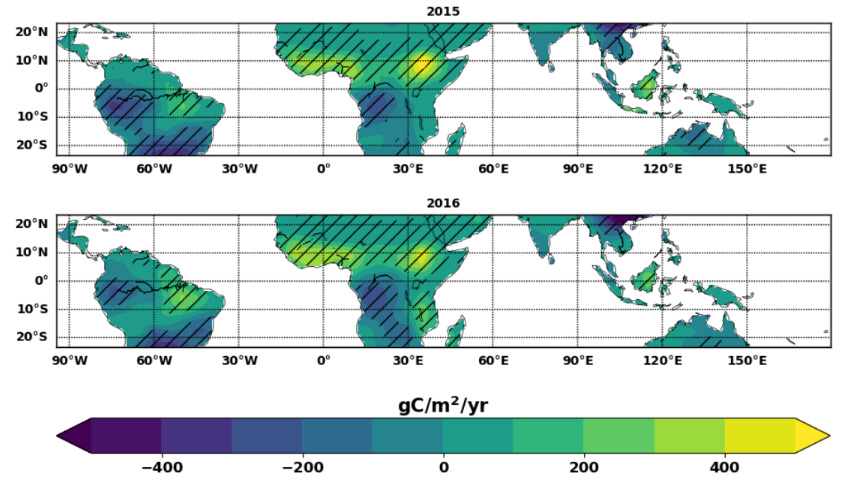

下圖取自該論文的補充資訊,顯示2015年和2016年熱帶土地的二氧化碳排放量。在地圖上,深藍色表示碳匯區域,而黃色顯示二氧化碳淨排放為正的區域。

地圖顯示,2015~2016年,剛果盆地是一個大型碳匯。該地區有全世界最大的熱帶泥炭地,面積大於英格蘭。2017年的研究發現,這塊泥炭地儲存的碳相當於美國20年的化石燃料碳排。

從地圖也可看出,非洲碳排集中在西部熱帶非洲和衣索比亞部分地區。

帕瑪說,這些地區是「大型土壤碳儲藏」的所在地,「這些地區的土地劣化和森林砍伐可能導致土壤侵蝕並釋放出部分儲碳。」「土壤有機碳含量高的地區若發生顯著的土地利用變化,便很可能從土壤中釋放碳。」

下圖顯示了2018年熱帶非洲的林損程度-林損也是一種土地利用變化。該資料來自世界森林觀察(Global Forest Watch),世界資源研究所(WRI)的線上森林監測系統。

該研究指出,在衣索比亞西部,大規模碳排可能是人類土地利用變化加上氣溫高於平均溫度的結果(高溫會導致土壤以更高的速率釋出二氧化碳)。

「我們發現,在衣索比亞西部,每月的二氧化碳通量會隨著溫度的升高、降水和『液態水當量厚度』下降而增加。衣索比亞西部也經歷了大規模和持續性的土地利用變化、地上生物量減少(植物損失)和土壤侵蝕。」

令人不安的跡象

未參與這份研究的里茲大學熱帶生態學主席飛利浦(Oliver Phillips)教授表示,非洲熱帶地區的二氧化碳大量釋出可能是受到2015~2016年間聖嬰現象的影響。

「2015、2016年的聖嬰現象是有記錄以來數一數二強烈的。我們已經知道2016年大氣中二氧化碳濃度增加速度空前地快,熱帶氣溫破紀錄。其他研究顯示,這跟熱帶土地碳排有關。」

「這份研究認為大部分排放來自熱帶非洲北部部分地區,而這些區域完整森林已經很少。2015、2016的聖嬰現象在非洲的一個特性是長時間高溫,該研究顯示,大量碳排的部分原因是土壤碳儲存釋出,這很令人不安。這表示著全球暖化風險加劇了大部分農業用地的碳排放。」

帕瑪說,這項研究呼應最近政府間氣候變遷專門委員會(IPCC)氣候變遷和土地的特別報告所提出的觀點:土地面臨越來越大的人類壓力,但土地也是氣候變遷問題的一個解決方案,而解決氣候變遷問題無法光靠土地,」IPCC主席Hoesung Lee表示。

研究科學家兼全球碳計畫(Global Carbon Project)主任坎納戴爾(Pep Canadell)博士說,這項研究「將焦點帶到在我們所知甚少的地區。」

然而,在熱帶非洲發現大量二氧化碳排放源並不表示全球二氧化碳排放量高於科學家所知。坎納戴爾說:

「因為我們的碳預算是大氣二氧化碳排放源和碳匯的質量平衡,我們非常清楚大氣中二氧化碳的濃度,如果出現過去沒有計算過的新來源,表示可能有其他排放源被高估或其他碳匯被低估。」

Africa's tropical land released close to 6bn tonnes of CO2 in 2016, according to data taken by satellites.

This means that, if Africa's tropical regions were a country, it would be the second largest emitter of CO2 in the world – ahead of the US, which currently emits 5.3bn tonnes of CO2 a year.

The region's 2016 emissions were "unexpectedly large", the authors write in Nature Communications. This is because the land surface is covered by tropical forests and peatlands, environments which typically absorb large amounts of CO2 from the atmosphere.

The high rate of CO2 loss in 2016 could be associated with a "strong" El Niño, scientists tell Carbon Brief. El Niño is a natural phenomenon that periodically affects weather in many parts of the world. In the African tropics, it can cause unusually high temperatures and drought.

Other causes of CO2 emissions could include "substantial land-use change", including deforestation and fires associated with agriculture, the study says.

Tropical turmoil

Africa is home to one third of the world's tropical rainforests. Tropical forests are capable of storing large amounts of CO2. This is because trees absorb carbon from the atmosphere during photosynthesis and then use it to grow new leaves, shoots and roots.

The continent is also home to around 3% of the world's peatlands, including the world's most extensive tropical peatland. Peatlands are water-logged environments that can hold huge stores of soil carbon.

Though the African tropics are a globally important carbon store, there have been few studies looking into the extent of year-to-year CO2 emissions from the land in this region.

The new study analyses data taken by two satellites that recorded CO2 emissions stemming from the Africa's tropical land from 2014-17. These satellites include Japan's greenhouse gases observing satellite (GOSAT) and NASA's orbiting carbon observatory (OCO-2).

Data taken from both satellites shows that some parts of tropical Africa's land are now releasing more CO2 into the atmosphere than they are able to absorb through their trees and soils, says study lead author Prof Paul Palmer, a researcher of geosciences from the University of Edinburgh. He tells Carbon Brief:

"This is a new perspective. Other satellites have reported widespread land degradation over this region but our study is the first to link surface processes to changes in CO2. What the data suggests is that the land is degrading in certain parts of tropical Africa to a point where it is beginning to release carbon."

Forest flux

The results show that net CO2 emissions from Africa's tropical land totalled 5.4bn tonnes and 6bn tonnes in 2015 and 2016, respectively. (This figure considers the difference between the amount of CO2 absorbed and emitted by the land.)

Across the tropics as a whole, net CO2 emissions reached 3.8bn tonnes and 5.9bn tonnes in 2015 and 2016, respectively.

This is because the CO2 emissions from tropical Africa were offset by other tropical regions, such as parts of South America, which acted as net removers of CO2 ("carbon sinks") between 2015 and 2016.

The maps below, taken from the paper's supplementary information, show the extent of CO2 emissions from tropical land in 2015 and 2016. On the map, dark blue shows regions that acted as carbon sinks while yellow shows regions that were net emitters of CO2.

The extent of CO2 emissions from tropical land in 2015 and 2016 in grammes of carbon per metre squared per year (gC/m2/yr). Dark blue shows regions that acted as carbon sinks while yellow shows regions that were net emitters of CO2. Hatching shows regions with lower relative uncertainty. Source: Supplementary Information, Palmer et al. (2019)

The map indicates that the Congo basin acted as a large carbon sink from 2015-16. This region is home to the world's most extensive tropical peatland, which covers an area larger than the size of England. Research released in 2017 found that the peatland holds the equivalent of 20 years' worth of fossil fuel emissions from the US.

The maps also show that CO2 losses from Africa were concentrated in western tropical Africa and over parts of Ethiopia.

These regions are home to "large soil carbon stores", Palmer says. Land degradation and deforestation in these areas could have caused soils to erode and release some of the carbon they hold, he says:

"Substantial changes in land use over a region with high levels of soil organic carbon are conditions that could potentially release carbon from the soils."

The map below shows the extent of forest loss – a type of land-use change – across tropical Africa in 2018. The data is from the Global Forest Watch, an online forest monitoring service from the World Resources Institute (WRI).

In western Ethiopia, large-scale CO2 loss could be a result of human land-use change and higher than average temperatures, the study says. (Warming can cause soils to release CO2 at a higher rate.) The paper says:

"We find that over western Ethiopia monthly CO2 fluxes increase when temperature rises, and when precipitation and ‘liquid water equivalent thickness' falls. Western Ethiopia has also experienced extensive and persistent land-use change with significant reductions in above-ground biomass [plant loss] and soil erosion.

"Continued land degradation and warming temperatures could potentially result in a large diffuse CO2 emission source with a temperature dependence."

The large loss of CO2 in the African tropics was likely influenced by the 2015/16 El Niño, says Prof Oliver Phillips, chair in tropical ecology at the University of Leeds, who was not involved in the study. He tells Carbon Brief:

"The 2015/16 was one of the strongest El Niño events on record. We already know that atmospheric concentrations of CO2 increased faster than ever before in 2016 and that tropical temperatures reached record levels. And other studies have shown that this was boosted in part by emissions from the tropical land.

"The current paper attributes remarkably large emissions to parts of northern tropical Africa which retain very little intact forest. A feature of the 2015-16 El Nino in Africa was sustained warming – and the paper's suggestion that the large emissions are partly be due to soil carbon stores being [lost] is troubling. It implies a risk of global heating aggravating CO2 emissions within large areas of mostly agricultural land."

The study "illustrates the point made" by the recent Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change's (IPCC) special report on climate change and land, Palmer says.

The report, which was covered in depth by Carbon Brief, found that "land is under growing human pressure and is part of the solution [to climate change] – but land cannot do it all," according to the IPCC's chair Hoesung Lee.

The research "has brought focus to a region of the world we know so little about", says Dr Pep Canadell, a research scientist and director of the Global Carbon Project, an independent project tracking worldwide emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases.

However, the discovery of a large source of CO2 emissions in tropical Africa does not mean that global CO2 emissions are higher than scientists thought, he explains to Carbon Brief:

"Because our carbon budget is a mass balance of sources and sinks constrained by the atmospheric CO2 concentration that we know very well, it means that if a new source appears that was not accounted before, another source might have been overestimated or sinks elsewhere are bigger than we estimated.

"The point being that the carbon burden in the atmosphere is not worse than we thought, just because a new source is discovered."

※ 全文及圖片詳見:Carbon Brief(CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)