Rhinos

Classification:

Order: Perissodactyla

Family: Rhinocerotidae

Genus: Diceros (African Black rhino)

Ceratotherium (African white rhino)

Rhinoceros (Indian rhino & Javan rhino)

Dicerorhinus (Sumatran rhino)

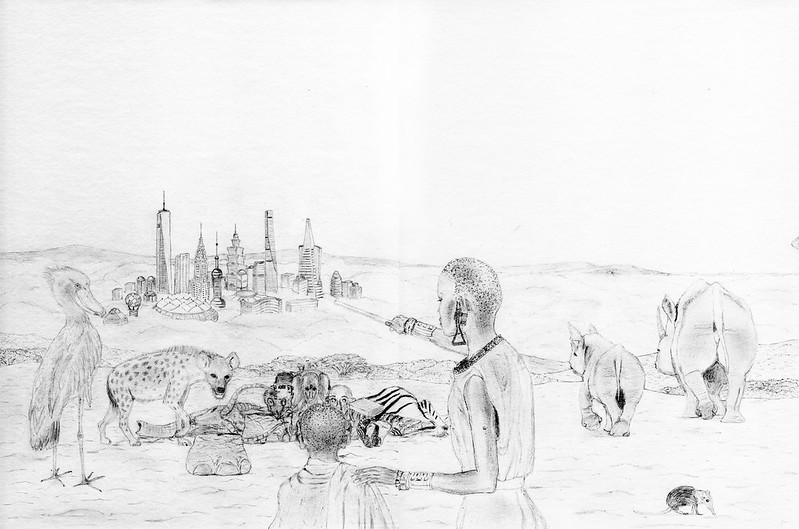

Characteristics: Last members of a thirty millions years old family

- Poaching for horns used in traditional medicine is the number one threat (Asia) [1]

- Habitat fragmentation

- Inbreeding and epidemics in small populations

- Poaching for horns used as ornaments (Yemen) [1]

This last threat is a consequence of the two others. It is particularly applicable to the Javan rhino. The remaining population can be found in a single location in Western Java and numbers around 40 individuals only [2].

Rhinos, mammals of Perissodactyla order:

Among herbivorous, members of the Perissodactyla order are much less numerous than the Artiodactyla. Today they are represented by horses (and their cousins donkeys and zebras) as well as tapirs and rhinoceros.

Perissodactyla have leg extremities supported by an uneven number of toes. From an evolutionary point of view, they differ from the larger order of the Artiodactyla. Those have their legs supported by an even number of toes. Artiodactyla include cows, sheeves, antelopes, pigs, giraffes.

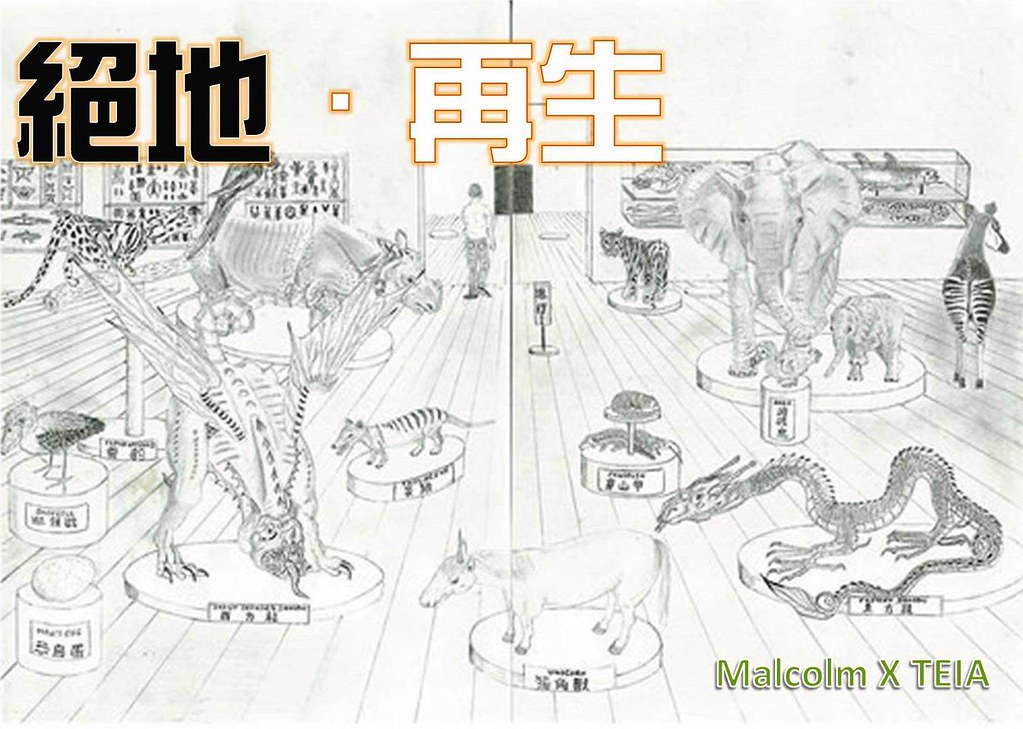

In the relatively small order of Perissodactyla, Rhinocerotidae is certainly the most threatened family. The five remaining species are protected, therefore hunting them is illegal.

Much ahead of habitat loss, the largest threat on Asian and African rhinos is poaching for their horns. In the last decades, this plague led to the local extinctions of several species.

This includes the extinctions of the Javan rhino in continental Asia and of the West African subspecies of the Black Rhino as recently as in 2011 [3].

As the smallest in size of all surviving members of the Rhinocerotidae family, the Sumatran rhino is particularly interesting as it is genetically closer to last ice age woolly rhino than it is to its living cousins. This means that the Sumatran rhino shares a genetic heritage closer to an extinct rhino adapted to a cold and dry climate than to the existing rhino species.

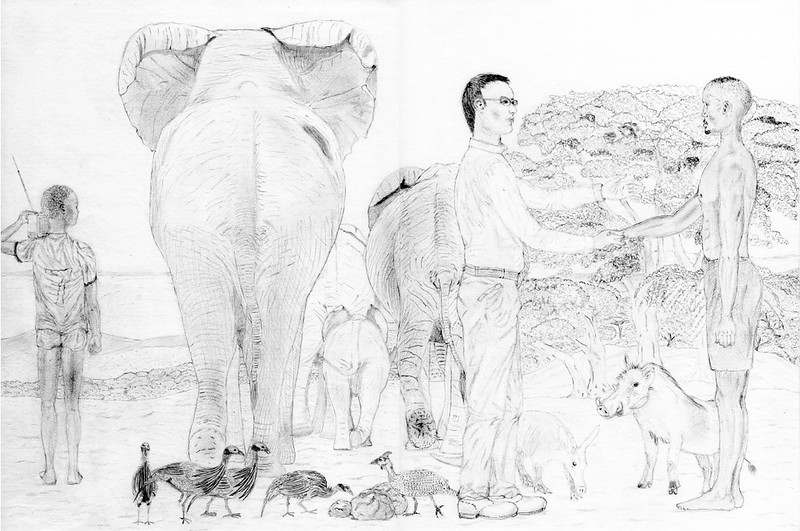

Rhinoceros have fascinated the western world since the very first reports of these animals were made by travelers. Without ever having seen a real specimen, Renaissance artist Albrecht Dürer made a woodcut of a rhinoceros, emphasizing the shield-like appearance of the animal’s skin. This woodcut is still considered to be a masterpiece of western fine arts today.

During the 18th century, a female Indian rhino travels to Europe. She was christened Clara and her fame spreads from England to Poland. From 1741 to 1758, people across Europe flock to see her and she is the object of such attention that most of the royal dignitaries and prominent scientists wanted to see her in person.

In Asia, the use of rhino horns in medicine is thought to be the major cause of their decline. This practice is a part of a centuries old tradition.

A Focus on insular rhinoceros

There are today two species of rhino that live on islands:

The Javan rhino Rhinoceros sondaicus and the Sumatran rhino Dicerorhinus sumatrensis.

Both species once thrived on the Asian continent in an area spanning from northeastern India to Indochina and southward to peninsula Malaysia.

The Sumatran rhino is the smallest of the three Asian species. It also belongs to a distinct genus that makes it closer to the last ice age rhinos than existing rhino species. A unique feature among rhinos is their distinctive hairy skin. Sumatran rhino calves are usually born with long reddish hair. Adult rhinos hair tend to shorten through abrasion in the wild.

The most endangered species, the Javan rhino, has now been fully extirpated from continental Asia and can only be found in a sanctuary in Java. The last continental population occurred in Vietnam and it is believed that a single population of over a dozen individuals was still remaining in Cat Tien National Park in the 1980’s. However, the last known specimen was found dead in 2010[4]. It had been shot dead and its horn had been removed.

A single population of between 37 and 44 individuals still survives in Ujung Kulon National Park [2], Western Java, Indonesia. This figure is extremely low, which makes the Javan rhino one of the most endangered mammals in the world and the most endangered of all of the remaining rhino species. Such a small population is particularly exposed to a loss of genetic diversity, making its long-term survival even more unlikely. Currently no Javan rhino populations exist in captivity, which means that there are no conservation programs aiming at securing an acceptable genetic diversity.

In comparison, the equally concerning Sumatran rhino situation is slightly less critical. Its total population in the wild is estimated between around 220-275 individuals[2]. However, securing viable populations implies more efforts for its conservation. The species can be found in scattered small populations, mainly in Sumatra but also in Borneo and in peninsular Malaysia. It is therefore still present on the Asian continent with a small remnant population in Taman Negara, Western Malaysia.

This species has been more closely studied than the Javan rhino due to the existence of a captive population. However, attempts to put in place conservation programs of captive animals have emphasized the challenges of such programs. In particular, the Malaysian captive population was decimated by a pest outbreak in 2003[5].

In all, from an initial captive population of 40 individuals worldwide in the 80’s, only two calves were born in Cincinnati zoo in 2001 and 2004. More than half of the initial captive populations have died since, showing a decrease even greater than the population in the wild!

What can I do as a simple citizen?

Fascination for rhinos has also been the cause of their doomed fate. Their distinctive appearance has been at the origin of cultural believes: The demand for Chinese medicine is today the driving force leading all rhino species to extinction.

In comparison, habitat reduction plays a more modest role in the global rhino population decrease.

As one of the last remaining representative of the Earth megafauna, they are a unique heritage that shall be passed to the future generations.

To give rhinos a chance, we should:

- Never use or buy any product made of rhino body parts or organs, whether it be medicine, a decorative item or a ritual item

- Support programs aimed at protecting the remaining rhino habitats

- Minimize or avoid the consumption of products that are conflicting with rhino’s natural habitat, if possible select products that are produced according to a chart of environmental responsibility

- And if you can afford it, support ecotourism and give your children the chance to see those wonderful animals in the wild. This includes ecotourism in countries such as Kenya, Tanzania, Zambia, Namibia and South Africa to spot the African white rhino and the rarer African black rhino. Closer to Taïwan, this includes Gunung Leuser National Park in Sumatra, Indonesia and the beautiful Danum Valley park of Sabah, Borneo, Western Malaysia for the Sumatran rhino and Ujung Kulon National park in western Java, Indonesia for the even rarer Javan rhino. The Indian rhino can still be spotted in Nepal Teraï area as well as in Indian Assam.

Differences and similarities between rhinos and tigers

The number one threat for both rhinos and tigers is the illegal trade of their body parts for Chinese medicine. However, the conservation status of rhino species is made even more difficult by several factors.

Tigers are represented by several subspecies, which have often interbred in captivity. This can be considered to be an issue since mixed individuals cannot take part in conservation programs of the different tiger subspecies. However, all individuals belong to a single species Panthera tigris.

Rhinos are represented by four different genuses. Only the Indian rhino and the Javan rhino are genetically close enough to belong to the same genus.

The reproduction of rhinos in captivity is much more difficult than it is for tigers. Births of rhino calves and survival into adulthood are still extremely rare events. In comparison, births in captivity have made the captive tigers populations sustainable and on an increasing trend.

The sexual maturity of a rhino is around 7 years for females, 10 years for males, gestation is not known precisely for all species but estimated to be around 14-19 months. There is only a single calf per litter. Female biological cycle allows her to be pregnant only every 2,5-3 years. This data emphasizes the very slow dynamic of rhino species, further explaining how hunting pressure on their population can have irreversible effects.

The table here below compares tiger and rhinos reproduction data [2],[6]:

| Worldwide population in captivity | Sexual maturity | Gestation | Average offsprings per litter | |

| Tigers | More than 10,000 | Female 3-4 years, male 4-5 years | Around 100 days | 2-4 cubs once every 2-2,5 years |

| Rhinos | Less than 1000 | Female 6-7 years, male 10-12 years | 14 to 19 months depending on species | One calf every 2,5-3 year |

[1] http://www.savetherhino.org/rhino_info/threats_to_rhino

[2] http://www.savetherhino.org/rhino_info/species_of_rhino

[3] http://www.iucnredlist.org/details/39319/0

[4] http://www.wwf.org.uk/about_wwf/press_centre/?unewsid=5367

[5] http://www.rhinoresourcecenter.com/pdf_files/117/1175857689.pdf

[6] http://www.tigers.org.za/birth-and-care-of-the-young.html#.VAPuDLAcTVI