The Takahē

Classification:

Order: Gruiformes

Family: Rallidae

Genus: Porphyrio

Species: P. hochstetteri

Estimated current population: around 350 individuals, status Endangered

Population trend: Increasing

Main Threats:

- Introduced mammal predators

- Introduced mammals competing for food

- Harsh winters

Characteristics: A giant flightless cousin of the common Moorhen…

The Takahē is a species of bird endemic to New Zealand. Its name comes from the Maori language, spoken by the Polynesian people who settled on the islands before the arrival of European people.

With a height reaching 50 cm and a weight of 3 kg, it is larger than any other member of the Rallidae family. Captive individuals can live up to 20 years, significantly longer than in the wild.

Similarly to the giant panda that has an exclusive diet of bamboo, the Takahē are specialized in one type of food only. They almost exclusively rely on a few species of tussock grass and if not available, they can feed on the starchy roots of ferns. As their staple food has a low energy value, they spend most of their time feeding.

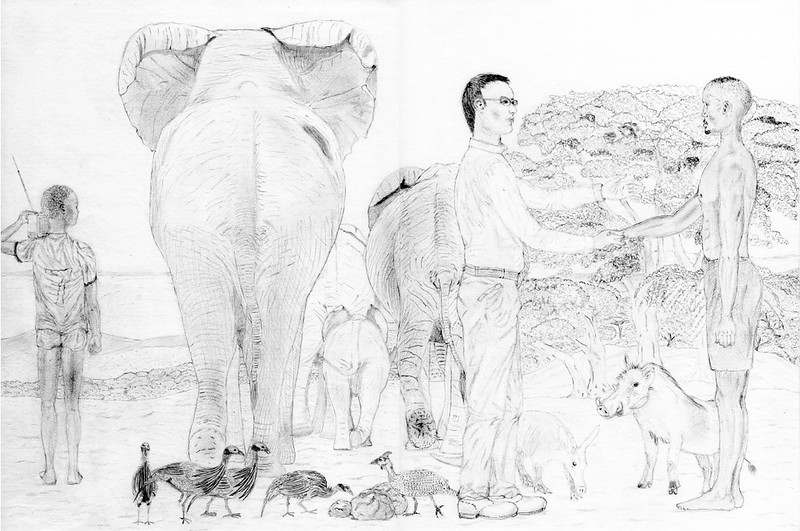

Because of its isolated location in the southern hemisphere, New Zealand had no land mammals until the arrival of the Maori people in the 13th century (bats were the only mammals present on the islands). In the absence of pressure of mammals, some birds developed specific features common to other insular birds. In particular, several genuses evolved into flightless birds, some of which also developed insular gigantism.

All moa birds, the tallest of these flightless birds disappeared shortly after the arrival of the Maori because of the hunting pressure. Kiwi birds are still present on the islands and all species are protected. The Takahē is the only Rallidae that became flightless on the archipelago.

It has therefore been particularly sensitive to land mammals introduced by humans, such as stoats, rats and pigs. The introduction of deers from Europe also adds a pressure on the species as they compete for food in the Takahē grassland habitat.

The Takahē seemed to be already in decline when the European settled on the islands in the 17th century. It became so rare that was considered as extinct at the beginning of the 20th century[1].

Several reasons have been adduced to explain the early decline of the flightless bird. If the arrival of humans and their imported land mammals had a significant impact, some scientists believe climate changes had already had a negative impact on its population[2].

1948…Rediscovery and Conservation

A group of less than 300 individuals was rediscovered in 1948 in alpine grasslands of the Southern Island, the Murchison Mountains[1]. It is not clear whether this harsh environment was the preferred habitat of the bird. It is suspected that this biotope constituted a last sanctuary relatively free of mammals.

It was initially decided to minimize human interference with the birds except for minimum scientific monitoring and deer control. However, it was acknowledged that this decision could not protect the birds on the long term as the population went on decreasing.

An ambitious conservation program was then put in place in the 80's. New Zealand is now at the forefront of conservation for this iconic species.

It is technically impossible to prevent intrusion of land predators in the original habitat as well as to control competition for food by other species. Despite a strict monitoring, the original population of 250-300 individuals has now stabilized around 160 individuals today. This shows how difficult the conservation of a vulnerable species is even when it is considered as a priority.

In order to increase the chances of survival, smaller populations were relocated to offshore islands with a strict control of land mammals. Captive populations also exist and are deemed necessary to ensure the long term survival of the species.

The long way to make the Takahē population viable

Due to the small gene pool of the Takahē, inbreeding is a constant threat, requiring a careful management of individuals and a control of nesting for the relocated populations.

In its original alpine habitat, the Takahē is threatened by predation. As recently as in 2007, an increase in the stoats (Mustela erminea) population had a strong toll on the bird, halving the wild population in a few months time only[1]. Stoats were introduced by Europeans in New Zealand to control mice populations at the end of the 19th century.

Introduced European deers (Cervus elaphus) have been competed with the bird for food to the point that culling programs have been put in place to control the mammal population.

Discussion:

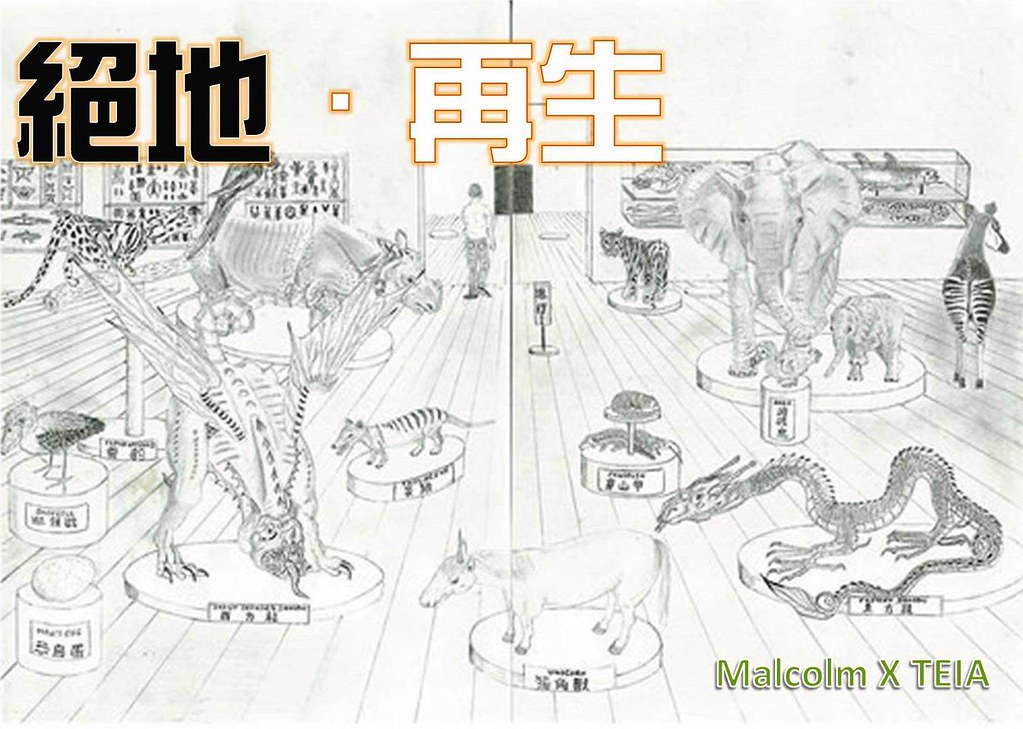

- Contrary to endangered large mammals such as the rhinos, the Takahē is not the target of an illegal trade. Its greatest enemy is not the human species itself but the drastic changes of its ecosystem.

- Having to cope with predators and competitors for food, the Takahē now needs the support of humans to survive. It clearly illustrates how sensitive ecosystems are to any foreign species introduction, especially on islands.

- Despite huge conservation means put in place, the Takahē population is increasing very slowly. Do you think such a program is justified?

- On a pure financial level, nations spend important amount of money on other topics, education, army, health, sport events.

More information:

- [1] http://www.doc.govt.nz/conservation/native-animals/birds/birds-a-z/takahe/threats/

- [2] Mills J.A., Lavers R.B. & Lee W.G. (1984) - The Takahe: A relict of the Pleistocene grassland avifauna of New Zealand - New Zealand Journal of Ecology