《氣候變遷和土地特別報告》深度QA系列3/3

(接續前篇)

「負排放」對土地、糧食和野生動植物有什麼好處?

IPCC的1.5°C報告的一項主要發現是,要將全球暖化控制在「安全限度」內,需要一定程度的「負排放」──「負排放」泛指從大氣中去除二氧化碳並儲存在陸地或海洋中的方法,涵蓋種樹等自然方法到機器吸碳等技術,稱為直接空氣捕獲(direct air capture,DAC)。

如果大規模應用,這些技術或多或少要用到土地,可能排擠野生動植物棲地和糧食用地。《氣候變遷和土地特別報告》強調,負排放非萬靈丹,若只是大規模部署單一技術,可能「增加沙漠化、土地劣化、糧食安全和永續發展風險」。

許多限制全球暖化在1.5°C的模擬途徑嚴重依賴「碳捕獲和儲存生物能」(BECCS)技術。 (有些研究發現,沒有BECCS也可以實現1.5°C目標,但要在其他方面有不同假設。)這種技術需要種植作物,利用作物產生能量,在能量儲存在地下或海洋前捕獲所產生的二氧化碳。有少數試點計畫實作了BECCS,但該技術尚未經實證可以大規模發揮作用。未來要運用多少BECCS將取決於一系列複雜的社會和技術因素。

然而,如果BECCS要以每年幾十億噸二氧化碳的規模從除去大氣中的二氧化碳,可能「增加土地壓力」並導致「土地劣化」。

根據「決策者摘要」(summary for policymakers, SPM),大規模種樹或造林也可能帶來風險。報告中提到,大規模植樹造林可能「增加土地用途改變的需求」並增加劣化的風險。

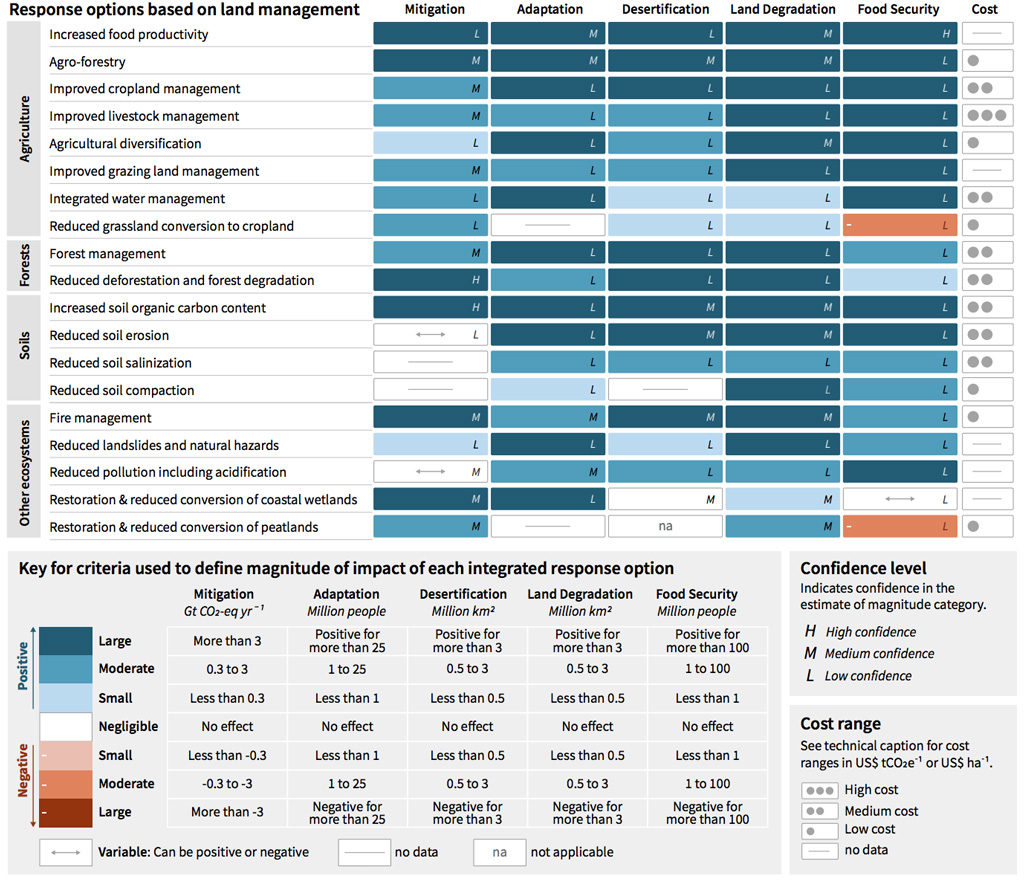

下圖來自SPM,總結不同吸碳方案的各種影響。圖中顯示每種方案從大氣中去除二氧化碳(「緩解」,第一欄)、幫助人們適應氣候變遷(「適應」,第二欄)、避免沙漠化(第三欄)、避免土地劣化(第四欄)和幫助糧食安全(第五欄)的能力。淺到深綠色表示正面影響,淺到深紅色表示負面影響。

實施該技術的潛在成本在最右側用點點表示。英文字母代表調查結果的信心水準(「L」代表低,「M」代表中等,「H」代表高)。

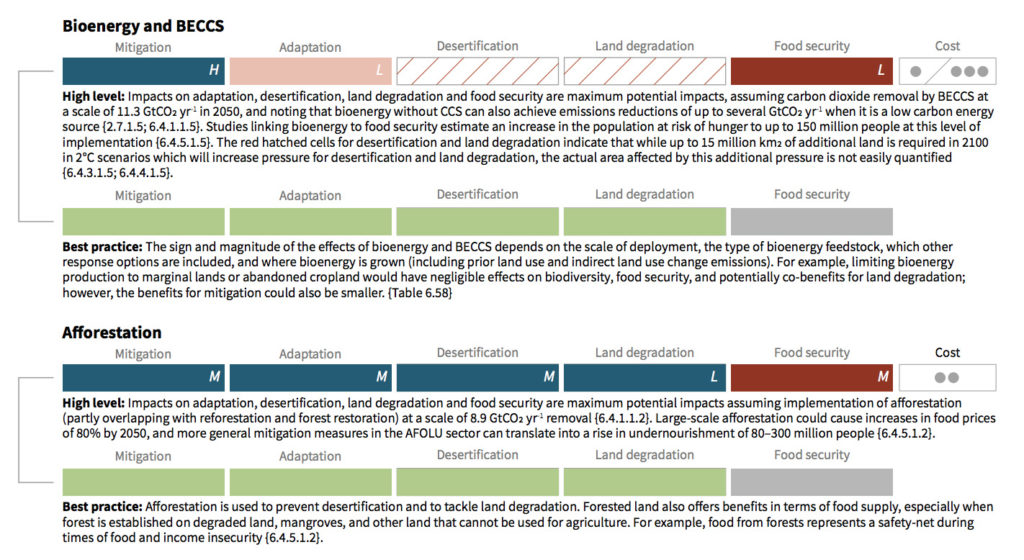

SPM第二張圖比較了BECCS(上圖)和植樹造林(下圖)等潛在全球技術的風險。圖中顯示如果僅「大量運用」某技術而非「最佳實踐」的風險。該圖顏色意義同上圖,也使用綠色表示潛在共同利益。

圖中顯示,「大量運用」BECCS和植樹造林都可能導致糧食安全高風險。「大量運用」BECCS對適應氣候變遷、沙漠化和土地劣化的風險還可能高於「大量運用」造林。

不過,如果較小規模的運用並採用「最佳實踐」,兩種方式都可以從大氣中去除二氧化碳,同時為人類和野生動物提供共同利益。SPM提到,「將以土地為基礎的緩解措施運用於有限的土地,有限度地取代其他土地用途,副作用較小,並可為適應、沙漠化、土地劣化或糧食安全帶來積極的共同利益。」

土地報告第二章主要作者、布里斯托大學環境變化首席研究員豪斯(Jo House)博士說,不僅是土地使用規模很重要,實作方式也是。

「其中許多方法都可達到永續,端看實務上如何執行。而且,若能以永續且整合性的方式實作,可以帶來許多共同利益。如果只是在非常大面積的土地上單一化種植,或在有沙漠化危機的土地上進行,那可能會產生更大的副作用。」他在英國記者會上說,「使用的土地面積越大,糧食安全的風險就越大。這不僅與規模有關,也與實作方式有關。這很重要:我們可以做得很好,可以做得很冒險。」

根據報告,還有其他技術可以從大氣中清除大量二氧化碳,同時加強糧食安全並防止劣化,包括減少目前的森林砍伐和森林劣化狀況,以及增加土壤的碳儲量。

圖中顯示,有許多農法可以移除大量二氧化碳,同時提供土地共生效益,包括提高糧食生產率、農林業和改善作物和牲畜管理,下面有更詳細的討論:「這些問題之間的關聯性?有哪些解決方案?」

報告強調,採用「整合性方法」,整合運用多種不同的土地負碳排技術,可以吸收大量二氧化碳,同時最大幅度降低對人類和野生動植物的風險。然而,許多吸碳方案仍有巨大的「經濟、技術、制度、社會文化、環境和地球物理障礙」。

如果繼續延後實施,土地負碳排方法從大氣中去除二氧化碳的整體能力可能會開始下降。如同第六章所提,「隨著氣候變遷的增加,一些土地管理方案的潛力會減少,例如,氣候可能會改變土壤和植被固碳的能力,減少了土壤有機碳增加的機會。」

這些問題之間的關聯性?有哪些解決方案?

正如報告所明確指出,氣候變遷、沙漠化、土地劣化和糧食不安全都是彼此重疊的問題,這些問題也與水資源供給和生物多樣性等更廣泛的問題密切相關。

報告第六章匯集了各方面的問題,並探討共同因應所有這些問題的方法,評估每種方案的可行性,以及因應未來氣候變遷的限制。

解決這些問題的策略包括減少食物浪費、種植更多樹木等,但每種策略都有自身的複雜度,通常有些必須考慮的副作用。此外還有重大的地域性差異,許多作法需要時間才能發揮效果。

報告也探討這種「整合性因應方案」將如何影響聯合國永續發展目標(SDGs)以及生物多樣性和生態系統服務政府間平台(IPBES)提出的自然對人類的貢獻概念(NCP)──總共討論了40個具體方案。其中8個方案為報告中談到的各種土地議題提供中到高度的利益,分別是提高糧食生產率、改善森林管理、減少砍伐森林、增加土壤有機碳含量、增強礦物風化、飲食習慣改變、減少收穫損失、減少食物浪費。

作者發現,大多數因應方案可在不競爭可用土地的情況下實施,包括改善作物管理和增加土壤碳含量。其他方法,如飲食習慣改變和減少食物浪費則可以釋出土地。整體而言,其中17個方案對SDGs或NCP沒有任何副作用。

第七章確立了不同解決方案的潛力後,報告繼續討論實施這些方案需要作出的政策決定。表7.5詳列可因應氣候變遷和土地各個彼此關聯的問題的政策、計畫和工具。

第六章列出土地利用的各種需要取捨之處後,作者認為,全球目前氣候政策和決策未能考量這些取捨。例如,作者注意到水力發電設施可能妨礙魚類活動,太陽能和風力發電場可能會影響瀕危物種並破壞棲息地。

其中浮現出的一個關鍵訊息是「只有將農業排放納入主流氣候政策,才能實現本報告中評估的所有減緩潛力」。報告的結論是,碳定價有機會透過市場或稅收減少溫室氣體排放,但報告也提醒,該產業的效果仍然相對缺少實證。

目前以土地為基礎的策略佔巴黎協定國家自主減排承諾總量的四分之一,許多方案已經在實施中。

SPM指出,許多策略在轉化為政策之前需要考慮當地的環境和社會經濟問題:「土壤碳管理等部分方法可能適用大多數土地利用類型,而有機土壤、泥炭地和濕地以及與淡水資源相關的土地管理實踐的效果取決於當地農業生態條件。」

淨零土地劣化是一個能帶來巨大利益但也深具挑戰性的目標,取決於「在地方、區域和國家層級,跨領域整合多種解決方案,包括農業、牧場、森林和水資源。

報告的結論是,一系列連貫的氣候和土地政策可推進巴黎協定目標和永續發展目標中的土地相關目標,並指出越早嚴肅採取行動越好。

然而,某些策略,如BECCS,距離大規模實作還有很長的路要走,而另一些則面臨重大的「政策遲滯」:「連部分一開始看起來能輕鬆達成的行動也窒礙難行,REDD+政策停滯不前就是個血淋淋的例子,說明這些解決方案非常需要足夠的資金、機構和地方的支持以及明確的成功指標。」

報告對永續發展、性別和原民社區的作用有何評論?

和1.5°C報告類似,土地報告非常強調因應氣候變遷與確保永續發展之間的相關。

報告的最後一章(第七章)專門討論因應氣候變遷的土地決策與永續發展的關係,指出氣候變遷和土地利用尤其威脅著全世界的窮人。

SPM表示,未來的土地相關氣候變遷政策需要經過精心設計,以盡量避免讓貧困人口面臨風險,「由於問題的複雜程度和參與解決土地問題的角色多元,達成永續土地管理和因應氣候變遷需要一整套而非單一政策,方可取得更好的成果。」

這反映了報告第六章,土地負碳排方法可能產生的影響。這章說,僅採用單一大規模負碳排技術可能會為人和野生動植物帶來重大風險。而且某些大規模土地負碳排,包括生物能源或BECCS,可能會與聯合國的部分永續發展目標衝突。如目標15,其目的是「保護、恢復和促進陸域生態系的永續利用,永續管理森林,防治沙漠化,抑制和扭轉土地劣化和生物多樣性喪失」。

有些土地負碳排技術可在減碳的同時為這個目標創造共同利益,包括避免砍伐森林、提高糧食生產力和增加土壤碳儲量。

SPM表示,氣候變遷相關經濟政策也可以往盡可能降低世界貧困人口風險的方向設計:「這些政策的要素可能包括天氣和健康保險、社會保護和適應性安全網,應急融資和儲備基金,預警系統補助以及有效的應變計畫。」

而在採取永續土地的氣候變遷解決方案方面,報告強調在其中進一步提升性別平等的重要性。第七章第87頁的註解如下:「性別是社會不平等的一項關鍵,與其他權力和邊緣化系統交會 ──包括種族、文化、階級/社會經濟地位、地理位置、性別和年齡 ,這導致氣候變遷韌性和適應能力的不平等。」

在農村地區,女性比男性更容易受到氣候變遷及土地解決方案的影響,只是方式不同。

例如,研究發現,在澳洲和加拿大的農場,調適氣候變遷的工作不成比例地落在女性頭上。在衣索比亞的研究則發現,戶長是男性的家庭,可以獲得比戶長是女性的家庭更多的調適措施。

第七章說,未來的氣候政策應該更充分意識到性別平等的需求。可以透過制定增強女性財務授權和土地所有權的政策來實現。

在整個報告中,多處提及當地知識(來自本土社群的知識)納入土地決策的重要性。

報告指出,缺乏長期紀錄資料時,原民知識能在理解氣候變遷對地區土地的影響上發揮關鍵作用。SPM提到,「根據原民和當地知識,氣候變遷正在影響乾旱地區的糧食安全,尤其是非洲、亞洲和南美洲的高山地區。」

聯合國原民權利問題特別報告員塔里寇培茲(Victoria Tauli-Corpuz)表示,原民參與解決方案制定是很重要的。他在報告發布前的記者會上說:「沒有人比原民和當地社群更了解糧食、燃料和森林之間的衝突。我們經常處於土地衝突的十字路口,尤其是森林。身為專家,我們常以數百年來累積的知識為指引,非常適合管理、保護和恢復世界森林。」

報告引起的迴響

IPCC土地特別報告引起全球媒體大幅報導。最初的新聞報導聚焦在多重風險相互交疊的性質。如衛報報導,報告指出氣候危機正在破壞土地供養人類的能力,隨著全球氣溫上升,連續風險變得越來越嚴重。美聯社報導,報告探討了全球暖化和土地如何地惡性循環。人為造成的氣候變遷正在大幅度劣化土地,人們使用土地的方式也正在加劇全球暖化。衛報的第二篇文章警告氣候變遷對土地的影響「威脅人類文明」。

糧食和飲食習慣也是報導焦點。Mother Jones報導,「氣候變遷對糧食、水和土地造成的損失比我們所知更嚴重。海峽時報報導,如果採取正確的農法,可以餵飽全球同時因應氣候變遷 。紐約時報頭條新聞稱「氣候變遷威脅世界糧食供給。BBC報導,轉向以植物為基礎的飲食有助於因應氣候變遷。泰晤士報標題寫道:「聯合國呼籲,少吃肉,救地球」,後續報導指出,減少食物浪費和少吃肉可以避免大片土地因農業而劣化,減少氣候變遷。

另一方面,NPR報導:「人類必須徹底改變糧食生產方式,以防止全球暖化造成災難。」路透社報導,「農業和飲食習慣必須改變,以遏制全球暖化。」華盛頓郵報和Hill亦有類似報導。

英國金融時報下標:「氣候報告警告陸地氣溫升高」,並指出陸地空氣暖化速度大約是全球平均的兩倍。

首波媒體報導後,許多非政府組織陸續發表對IPCC報告的回應。

世界自然基金會(WWF)氣候變遷首席顧問兼IPCC負責人科尼利厄斯(Stephen Cornelius)指出:「報告明確地表示,我們目前使用土地的方式正在助長氣候變遷,同時削弱了土地支持人與自然的能力。」「我們需要立即改變使用土地的方式。優先工作包括保護和恢復自然生態系,以及實現永續糧食生產和消費。」

氣候行動網(CAN)歐洲主任特里歐(Wendel Trio)提醒:「從報告可看出,若以升溫1.5°C為目標,就必須採取行動以避免破壞糧食鏈。」「頻繁的乾旱、洪水、熱浪和野火,讓許多歐洲農民減產和收入減少。其中有些人已經撐不下去。」

有些非政府組織強調報告中關於利用土地吸收和儲存碳的內容。英國皇家鳥會(RSPB)保育主任哈潑(Martin Harper)說:「以自然為基礎的解決方案不僅是恢復世界自然財富的機會,還有助於抑制氣候變遷。」

有些非政府組織特別關注土地需求衝突的平衡。基督教救助協會(Christian Aid)全球氣候主任克萊摩(Katherine Kramer)博士說:「報告呼籲我們為人類、自然和氣候更妥善地管理土地。在土地利用方式上創造雙贏的方法很多,但我們必須盡快行動,以避免在餵飽人口和減少排放之間取捨。」

其他非政府組織對報告中負碳排技術內容的評論更為直白。 ActionAid的氣候政策協調員安德森(Teresa Anderson)說:「報告發出了嚴肅的警吿-依賴生物能源、碳捕獲和儲存等危險技術,將佔用大量土地,與我們改善糧食安全和保護自然生態系統的需求背道而馳。」「富裕的污染國不能指望南營放棄大片農田來解決氣候問題。」

CAN生態系統協調員普特(Peg Putt)說BECCS是「生態系統、人類和糧食安全的重大威脅」,「我們顯然無法承受失去或破壞重要生態系統的代價,該報告明確指出大規模開發生物能源和BECCS是不能接受也不可行的。」

350.org研究和募款協調員伊格斯(Mahir Ilgaz)也警告,「錯誤的解決方案將帶給生病的土地和生物多樣性更大的壓力」。「我們需要尋求不迫使人們離開自己土地的選項,也不能用生物多樣性換取更多的單一化栽培和工業化農業。」

保育機構Fern的生物能源活動負責人路德馬(Linde Zuidema)表示,該報告「呼籲政府逐步淘汰導致森林砍伐和森林劣化的有害補貼」,「這表示歐盟應該逐步取消對生物能源的補貼,轉而關注促進森林的保護和復育,這已經證實有益於自然和人類。」

Drax集團執行長加迪納(Will Gardiner)則認為,「BECCS是因應全球氣候緊急情況的必要技術」,該集團已逐步將其位於Drax的燃煤發電站改為燃燒木屑顆粒。

部分科學機構及其主要研究人員也發表聲明回應報告。波茨坦氣候影響研究所(PIK)主任洛克斯壯(Johan Rockström)教授說:「IPCC土地報告證實,我們正面臨全球性的緊急情況,能採取重要行動的時間越來越短,無所作為的代價將是災難。雖然報告描述了可能的淒慘後果,但也指明了前進的方向,包括立即採取行動的機會。」

全球公共與氣候變化墨卡托研究所福斯(Sabine Fuss)教授警告,「如果農業(佔所有溫室氣體排放量的五分之一)無法快速變革,可能會導致嚴重的土地使用競爭。」「到時就必須大規模地從大氣中去除碳,以造林或生物能源的方式,這可能就得犧牲糧食供給或生物多樣性。」

里茲大學(University of Leeds)氣候變遷福斯特(Piers Forster)教授也提出類似觀點,「為了將升溫限制在1.5°C以下,我們需要大幅改變使用土地的方式……簡言之,我們需要更少的牧場、更多的樹木,實際上這表示我們更加仔細地考慮如何使用每英畝的土地。土地要用來種植糧食,提供生物多樣性和淡水,為數十億人提供工作,並吸收數十億噸碳。」

東英吉利大學皇家學會氣候變遷科學教授、英國氣候變遷委員會(CCC)成員拉奎爾(Corinne Le Quéré)教授表示,「IPCC的調查結果與CCC給政府的建議一致,英國需要減少食物浪費、鼓勵健康飲食,並永續地使用土地,包括種植更多的樹木和復育劣化的土壤。所有這些方法都將有助改善人們的生活,同時減少導致氣候變遷的有害排放。」(系列專文3/3,完)

How could 'negative emissions' affect land, food and wildlife?

A major finding of the IPCC's landmark 1.5C report was that some degree of "negative emissions" will be needed to keep global warming within "safe limits".

"Negative emissions" are a group of methods that aim to remove CO2 from the atmosphere and store it in the land or ocean. They range from the natural-sounding – planting trees, for example – to the technologically advanced, such as using machines to suck CO2 from the air (known as direct air capture, or DAC).

If pursued at scale, most of these techniques would require varying amounts of land – potentially reducing the land left for wildlife and food production.

The land report emphasises that there is no one "silver bullet" when it comes to negative emissions and that, if just one technique were deployed on a vast scale, it could "increase risks for desertification, land degradation, food security and sustainable development".

Many of the modelled pathways for limiting global warming to 1.5C rely heavily on a technique called "bioenergy with carbon capture and storage" (BECCS). (Some research has suggested the 1.5C target can be achieved without BECCS, but only under stretching assumptions for change elsewhere.)

This technique involves growing crops, using them to produce energy and then capturing the resulting CO2 emissions before storing them in the ground or sea. A small number of pilot projects carry out BECCS – but the technique has not yet been proven to work at scale.

How much BECCS is used in the future will depend on a range of complex social and technical factors, the report says. (To read more about the world's possible future socioeconomic pathways, please see: "How important are socioeconomic changes for future land degradation?")

However, if BECCS is pursued at the level "necessary to remove CO2 from the atmosphere at the scale of several billion tonnes of CO2 per year", it could "increase pressure on land" and cause "land degradation", the report says.

Widespread tree planting – also known as "afforestation" – could also come with risks, the SPM says. Large-scale afforestation could "increase demand for land conversion" and raise risks of degradation, the report says.

The graphic below, taken from the SPM, gives an overview of the various impacts of different options for removing CO2 from the atmosphere.

For each technique, the graphic gives an idea of its ability to remove CO2 from the atmosphere ("mitigation"; first column); to help people adapt to climate change ("adaptation"; second column); to avoid desertification (third column); to avoid land degradation (fourth column) and to aid food security (fifth column).

Light to dark turquoise illustrate that the technique has a positive impact in these areas, whereas light to dark red represent a negative impact. (More detail on the scale of impacts is offered in the key.)

The potential cost of implementing the technique is shown with dots on the far right-hand side. Letters represent the level of confidence in the findings (with "L" representing low, "M" representing medium and "H" representing high).

A graphic giving an overview of the potential impacts of various techniques for removing CO2 from the atmosphere. Light to dark turquoise illustrate that the technique has a positive impact in these areas, whereas light to dark red represent a negative impact. The potential cost of implementing the technique is shown with dots on the far right-hand side. Letters represent the level of confidence in the findings (with "L" representing low, "M" representing medium and "H" representing high). Source: Adapted from SPM.3A of the IPCC land report.

A second figure in the SPM compares the risks of potentially global techniques such as BECCS (top) and afforestation (bottom). This figure shows the risks if the techniques are used at a "high level" versus if they are used at "best practice". This figure makes use of the same colour scale as the previous figure but also uses green to signify potential co-benefits.

Comparison of the risks of bioenergy and BECCS and afforestation when implemented at a "high level" versus at "best practice". Dark turquoise illustrates that the technique has a positive impact in these areas, whereas light to dark red represents a negative impact. Green signifies the possibility of co-benefits for each area. The potential cost of implementing the technique is shown with dots on the far right-hand side. Letters represent the level of confidence in the findings (with "L" representing low, "M" representing medium and "H" representing high). Source: Adapted from SPM.3B of the IPCC land report.

The figure shows that both "high level" BECCS and afforestation could come with high risks for food security. The figure also shows, however, that risks to climate change adaptation, desertification and land degradation could be higher with "high level" BECCS than with "high level" afforestation.

If deployed on smaller scales and with "best practice", however, both options could remove CO2 from the atmosphere while providing "co-benefits" for people and wildlife, the SPM says:

"Applied on a limited share of total land, land-based mitigation measures that displace other land uses have fewer adverse side-effects and can have positive co-benefits for adaptation, desertification, land degradation or food security."

For both techniques, it is not just the scale of land used that will be important, but also the way in which they are carried out, says Dr Jo House, lead author of chapter two of the land report and a lead researcher of environmental change from the University of Bristol. She tells a press conference for UK journalists:

"Many of these options can be sustainable depending on the way that we do them. And, if they are done in an integrated sustainable way they could have many co-benefits. However, if they are done on very, very large areas of land and with monocultures, and on areas of land that are already sensitive to desertification, that could have greater impacts.

"The more area of land that is taken, the more risks there are for food security. But it's not just about the scale, it is also about the way in which we do things. That's the really important message: we could do things well or we could do things in a way that increases risks."

There are also several techniques that could, according to the report, remove large quantities of CO2 from the atmosphere while enhancing food security and protecting against degradation.

These include reducing current levels of deforestation and forest degradation and boosting the carbon stores of soils.

Many options exist within agriculture to remove large quantities of CO2 while providing co-benefits for the land, the graphic shows. Such techniques, including increasing food productivity, agro-forestry and improving the management of crops and livestock, are mentioned in more detail below under: "How are the issues linked and what solutions exist?"

The report emphasises that pursuing an "integrated approach" – involving many different land-based negative emissions techniques, could deliver large CO2 removal while minimising risks to people and wildlife.

However, many options for CO2 removal still face large "economic, technological, institutional, socio-cultural, environmental and geophysical barriers", the report says.

If delays to deployment continue, the overall ability of land-based negative emissions to remove CO2 from the atmosphere could start to decrease, says chapter six:

"The potential for some land management options decreases as climate change increases; for example, climate alters the sink capacity for soil and vegetation carbon sequestration, reducing the potential for increased soil organic carbon."

How are the issues linked and what solutions exist?

As the report makes clear, climate change, desertification, land degradation and food insecurity are all overlapping challenges that also tie into wider concerns such as water availability and biodiversity.

Chapter six of the report draws together the various strands, and considers ways to deal with all of these challenges together. The feasibility of each option is assessed, as well as its vulnerability to future climate change.

Strategies to address these issues range from cutting food waste to planting more trees, but each one comes with its own complications, the report notes, often including adverse side-effects that must be taken into consideration. There are also significant regional differences, and the authors note that many of the responses will take time to be effective.

It also considers how such "integrated response options" would affect the UN's sustainable development goals (SDGs) and the concept of nature's contributions to people (NCP) laid out by the Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

In total, the report considers 40 specific responses to the issues. Eight of these options yielded medium to large benefits for all of the land challenges being considered: increased food productivity; improved forest management; reduced deforestation; increased soil organic carbon content; enhanced mineral weathering; dietary changes; reduced post-harvest losses; and reduced food waste.

The authors found that "most response options" can be implemented without competing for available land, including improvements to crop management and increasing the carbon content of soils. Others, such as dietary changes and cuts to food waste will actively free up land.

It also finds that, overall, 17 of the strategies could be delivered with no adverse side effects for either SDGs or NCPs.

Having established the potential of different responses to the challenges the planet faces, in chapter seven of the report, it goes on to consider the policy decisions that would need to be made to implement them.

Table 7.5 details policies, programmes and instruments that could be implemented to deal with each of the interlocking issues around climate change and land.

After identifying the various trade-offs in land use in chapter six, they acknowledge that for the most part globally "trade-offs currently do not figure into climate policies and decision making". By way of example, they note that hydropower installations can hamper the movements of fish, and solar and wind farms can affect endangered species and disrupt habitats.

One key message emerging is that "the full mitigation potential assessed in this report will only be realised if agricultural emissions are included in mainstream climate policy". The report concludes that carbon pricing, through markets or taxation, has the potential to cut greenhouse gas emissions while noting it is still relatively untested in this sector.

Many measures are already being implemented, with land-based strategies currently covering up to a quarter of the total mitigation proposed by nations' Nationally Determined Contributions submitted under the Paris Agreement.

The SPM notes that many strategies will require consideration of local environmental and socioeconomic issues before being translated into policy:

"Some options such as soil carbon management are potentially applicable across a broad range of land use types, whereas the efficacy of land management practices relating to organic soils, peatlands and wetlands, and those linked to freshwater resources, depends on specific agro-ecological conditions."

Land degradation neutrality [see Carbon Brief's recent piece on desertification for more on this], is a target with huge benefits but also a major challenge, and one the report says depends on the "integration of multiple responses across local, regional and national scales, multiple sectors including agriculture, pasture, forest and water".

The report concludes that a "suite of coherent climate and land policies" would both advance the goal of the Paris Agreement and the land-related targets of the SDGs, noting that the earlier serious action is taken, the better.

However, it also points out that some strategies, such as BECCS, are a long way from being realised on a large scale, while others face significant "policy lags":

"Even some actions that initially seemed like 'easy wins' have been challenging to implement, with stalled policies for REDD+ providing clear examples of how response options need sufficient funding, institutional support, local buy-in, and clear metrics for success, among other necessary enabling conditions."

What does the report say about sustainable development, gender and the role of indigenous communities?

In a similar vein to the 1.5C report, the land report has a heavy emphasis on the links between addressing climate change and ensuring sustainable development.

The final chapter of the report (chapter seven) is devoted to how land-based decisions for tackling climate change tie-in with sustainable development.

Climate change and land use particularly threaten the world's poor, the report notes.

Future policies for tackling climate change involving the land will need to be carefully designed in order to minimise risks for those living in poverty, the SPM says:

"Due to the complexity of challenges and the diversity of actors involved in addressing land challenges, a mix of policies, rather than single policy approaches, can deliver improved results in addressing the complex challenges of sustainable land management and climate change."

This language mirrors that of the chapter six of the report, which looks at the possible impacts of land-based "negative emissions".

This chapter says that pursuing just one negative emissions technique on a very large scale could come with significant risks for people and wildlife.

It also notes some options for large-scale land-based CO2 removal, including bioenergy or BECCS, could come with trade-offs for several of the UN's sustainable development goals.

Among goals that could be negatively affected is goal 15, which aims to "protect, restore and promote sustainable use of terrestrial ecosystems, sustainably manage forests, combat desertification, and halt and reverse land degradation and halt biodiversity loss".

However, several other land-based negative emissions techniques could remove CO2 while providing co-benefits for this goal, the report says. These include avoiding further deforestation, increasing food productivity and boosting the carbon stores of soils.

(For more information, see: "How could 'negative emissions' impact land, food and wildlife?")

Economic policies for tackling change, too, could be designed in such a way as to minimise the risks to the world's poor, the SPM says:

"Elements of such policy mixes may include weather and health insurance, social protection and adaptive safety nets, contingent finance and reserve funds, universal access to early warning systems combined with effective contingency plans."

The report notes the importance of attaining greater levels of gender equity in sustainable land-based solutions for tackling climate change. A box on gender on page 87 of chapter seven reads:

"Gender is a key axis of social inequality that intersects with other systems of power and marginalisation – including 'race', culture, class/socioeconomic status, location, sexuality, and age – to cause unequal experiences of climate change vulnerability and adaptive capacity."

The report says that, in rural areas, women face higher vulnerability to climate change and its potential land-based solutions than men – "albeit through different pathways".

For example, research has found that the need to adapt to climate change on farms in Australia and Canada falls disproportionately on women's workloads, the report says. In Ethiopia, research found that male-headed households had access to a wider set of adaptation measures than female-headed households, it adds.

Future climate policies should recognise the need for greater gender equality, chapter seven says. This could be achieved through designing policy that enhances female financial empowerment and land ownership, it says.

Throughout the report, there are many references to the importance of including local knowledge – particularly from indigenious communities – in land-based decision making.

The report notes that indigenous knowledge can play a key role in understanding the impacts of climate change on land in regions without long-term instrumental data records. The SPM says:

"Based on indigenous and local knowledge, climate change is affecting food security in drylands, particularly those in Africa, and high mountain regions of Asia and South America."

Greater involvement of indigenous people in the solutions needed to tackle these impacts is vital, says Victoria Tauli-Corpuz, UN special rapporteur on the rights of indigenous peoples. During a press conference held before the report's release, she said:

"No one knows the conflicts playing out among food, fuel and forests better than indigenous peoples and local communities. We're often in the crosshairs of conflicts over land, especially forests. As experts, often guided by hundreds of years of knowledge, we are uniquely suited to manage, protect and restore the world's forests."

What has the reaction been?

There has been extensive global media coverage of the report. (See Carbon Brief's media summary in today's daily briefing newsletter.)

Much of the initial news reports focused on the overlapping nature of risks that the report identified. The Guardian says the report warns that "the climate crisis is damaging the ability of the land to sustain humanity, with cascading risks becoming increasingly severe as global temperatures rise". The Associated Press says the "report examines how global warming and land interact in a vicious cycle. Human-caused climate change is dramatically degrading the land, while the way people use the land is making global warming worse". A second Guardian article warns the impacts of climate change on land "threaten civilisation".

Food and diets also featured prominently in the coverage. Mother Jones's coverage says "climate change is taking a bigger toll on our food, water and land than we realised", while the Straits Times says the world can "feed itself [and] fight climate change if it adopts the right recipe for farming".

Similarly, a New York Times headline says that "climate change threatens the world's food supply". BBC News says that according to the report, a shift to "a plant-based diet can help fight climate change". The Times headline reads: "Eat less meat to save the Earth, urges UN," with the accompanying article noting that cutting food waste and eating less meat could reduce climate change by saving large areas of land from being "degraded by farming".

Elsewhere, NPR begins its coverage of the IPCC findings by saying: "Humans must drastically alter food production in order to prevent the most catastrophic effects of global warming." Reuters reports that "farming and eating need to change to curb global warming", according to the IPCC, with the Washington Post and the Hill taking a similar line.

The Financial Times bucks the trend by running its coverage under the headline: "Climate report warns of rising air over land temperatures," noting that the air over land is warming roughly twice as fast as the global average.

With the initial wave of media coverage, numerous NGOs have released statements in response to the IPCC report.

It "sends a clear message that the way we currently use land is contributing to climate change, while also undermining its ability to support people and nature", says Stephen Cornelius, chief advisor on climate change and IPCC lead at WWF:

"We need to see an urgent transformation in our land use. Priorities include protecting and restoring natural ecosystems and moving to sustainable food production and consumption."

The report "shows that ramping up action in line with the goal to keep temperature rise to 1.5C is crucial to avoid massive disruption to our food chains", says Wendel Trio, director of Climate Action Network (CAN) Europe:

"Already now many farmers in Europe lose their production and revenue due to frequent droughts, floods, heat waves and wildfires. Some of them cannot adapt anymore."

A number of NGOs pick up on what the report says about using the land to absorb and store greater amounts of carbon. Martin Harper, RSPB director of conservation, says:

"Nature-based solutions offer the opportunity to not only restore the natural riches of the world but to also slam the brakes on climate change."

A particular focus for NGOs is the need to balance competing demands for land. As Christian Aid's global climate lead Dr Katherine Kramer puts it:

"Today's report is a clarion call for the need for us to manage land better for people, nature and the climate. There are many opportunities to create win-wins in the ways we use the land, but it's vital we implement these quickly to avoid having to make bleak choices between feeding people and reducing emissions."

Other NGOs are more frank in their assessment of what the report says about negative emissions techniques. Teresa Anderson, ActionAid's climate policy coordinator, says:

"It sends a stark warning that relying on harmful technologies such as bioenergy with carbon capture and storage, which would take up huge amounts of land, are at odds with our need to improve food security and protect our natural ecosystems.

"Rich, polluting countries cannot expect the Global South to give away swathes of farmland to clean up the climate mess."

And Peg Putt, ecosystems coordinator at Climate Action Network, describes BECCS as an "enormous threat to ecosystems, people, and food security", adding:

"As we clearly cannot afford to lose or destroy ecosystems vital to life, the report effectively paints large scale bioenergy and BECCS as completely unacceptable and unworkable."

Mahir Ilgaz, research and grants coordinator at 350.org, also cautions that "false solutions to the climate crisis will add even more pressure to our ailing land and biodiversity systems". Ilgaz says:

"We will need to pursue options that do not force people off their lands and do not swap biodiversity with more monocultures and industrial agriculture."

Linde Zuidema, bioenergy campaigner at Fern, says the report "calls on governments to phase-out harmful subsidies that drive deforestation and forest degradation". Zuidema adds:

"This means the EU should phase out subsidies for bioenergy and focus instead on promoting protection and restoration of forests – which has proven to be positive for nature and people."

In contrast, Will Gardiner – chief executive of the Drax Group, which has gradually been converting its coal-fired power station at Drax to burn wood pellets – argues that the report confirms that "BECCS is an essential technology in tackling the climate emergency the world is facing".

Some scientific institutions and their lead researchers have also put out statements in response to the report. Prof Johan Rockström, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impacts Research (PIK), says:

"The IPCC report on land confirms that we are facing a planetary emergency, that the window for taking decisive action is closing fast and that the costs of inaction will be catastrophic. While the report paints a bleak picture of what could come to pass, it also points a way forward, including opportunities for immediate action."

Prof Sabine Fuss from the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change warns that "if the rapid transition in agriculture, which accounts for about a fifth of all greenhouse gas emissions, does not succeed, it may result in serious land use competition". She adds:

"At that point, carbon will have to be removed from the atmosphere at large scale, for example through reforestation or cultivation of biomass for bioenergy, which could come at the expense of sufficient food supplies or conserving natural biodiversity."

Prof Piers Forster, professor of climate change at the University of Leeds, strikes a similar tone. The report "shows that to limit temperature change below 1.5C, we need to substantially change the way we use our land", he says:

"In a nutshell we need less pasture and more trees, but really it means thinking much harder about how we use every acre of land. Land needs to grow our food, provide biodiversity and freshwater, give work to billions of people, and suck up billions of tonnes of carbon."

And Prof Corinne Le Quéré, Royal Society professor of climate change science at the University of East Anglia and member of the UK's Committee on Climate Change (CCC) says the "IPCC's findings chime with our [the CCC's] advice to government":

"The UK needs to reduce food waste, promote healthy diets, and use land sustainably, including planting more trees and restoring degraded soils. All of these steps will help to improve people's lives whilst reducing the harmful emissions which cause climate change."

※ 全文及圖片詳見:Carbon Brief(CC BY-NC-ND 4.0)